Nigeria. Charismatic Islam surprises Lagos.

In the country’s most populous city, Muslim prayer groups have adapted to a scenario marked by the growth of Pentecostal Churches. Borrowing aspirations and rituals of a spiritual sentiment far removed from the traditional Islamic world.

Lagos, one of the most complex realities in West Africa, defies easy classification. Extending over 1,000 square kilometres, the megalopolis presents an intricate mosaic of seemingly contrasting yet interdependent realities. It is precisely in the megalopolis of Lagos that the multifaceted panorama of a newborn nation like Nigeria unfolds, where different realities seem to coexist in an apparent balance in a condition of continuous dynamism.

One of these changing realities is certainly that of religion. To understand its fluidity, it is necessary to start from the 1970s, a period that marks a significant turning point in the evolution of the nation. It was precisely in those years that Nigeria freed itself from the authoritarianism of the military government, beginning a period of fragile and unstable civilian governments. This step will not only open the way to conflicts of a political nature but also above all religious ones.

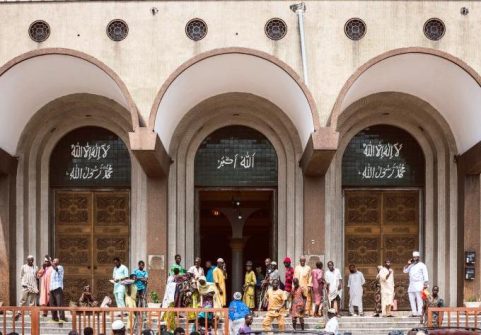

Lagos. Muslims attending Friday prayers, during the holy month of Ramadan at Lagos Island Central. Shutterstock/ Tolu Owoeye

During the decade in question, Nigeria experienced a period of unexpected economic good fortune thanks to its oil. The country did benefit from the embargo on crude oil imposed since 1973 by OPEC members on nations close to Israel, in the context of the tensions triggered by the Yom Kippur War. However, towards the 1980s, a series of endogenous factors, together with the collapse of the price of oil due to the discovery of new energy resources, determined the abrupt end of the Nigerian economic boom. These were also the years of the Structural Adjustment Plans that affected the whole of Africa: international financial institutions condition support for developing countries on the adoption of neoliberal economic policies. Also in Nigeria, this translates into strong privatizations in the public sector, increased economic inequalities and a general economic crisis felt by the population.

The growth of the “Gospel of Prosperity”.

It is precisely in this context of crisis and instability that the rapid success of Pentecostalism takes place, capable of providing hope to the needs of a population now disillusioned with the state and its institutions. The “prosperity gospel” preached by Pentecostal churches offers a message of salvation, economic well-being and individual empowerment, a rhetoric that the country desperately needs.

The promise of an inevitable divine intervention through prayer and the revelation of a subsequent miracle capable of improving the condition, even material, of the individual translates into the affirmation of the doctrine of prosperity even on the public scene.

It is in Lagos, that Muslims, perceive the need for change. 123rf

Aspiring politicians are beginning to see Pentecostal groups as an electoral resource to turn to, and some are actually able to succeed thanks to their political support.The progressive insinuation of Pentecostalism into the private and public life of the nation ends up causing concern among members of the Muslim community. The protagonism of this new form of charismatic Christianity pushes Islam into profound introspection, reevaluating its position and influence in society. However, it is not simply opposition between two religions competing for the public scene: Islam, in Nigeria, chooses a different path; adopting a strategy that Islamic orthodoxy would consider as “Bid’ah“, an unacceptable and aberrant modification of the religion.

The Nasfat

It is in Lagos, an important crucible of religious realities, that Muslims, especially those who speak Yoruba, perceive the need for change. New ideas therefore began to mature within Islamic prayer groups as early as the 1980s, becoming more widespread starting from the 1990s, as in the case of the Nasrul-lahi-li Fathi Society of Nigeria, or Nasfat.Founded by a group of bankers educated in Ibadan, Nasfat positioned itself as the promoter of an “Islamic renaissance” that would also influence subsequent groups.In the Nasfat mosques, we observe the pinnacle of a charismatic interpretation of Islam, where the imams adopt attitudes and preaching styles similar to those of Pentecostal pastors. The threat of the effectiveness of Christian propaganda, capable of recruiting new believers, is strongly perceived and manifests itself in the clear attempt to learn and employ charismatic pathos in one’s mission of “Dawa” (proselytizing action).

Muslim faithful praying under a bridge in Lagos. Shutterstock/ Oluwafemi Dawodu

This is how around Lagos, next to the advertising signs where sermons and meetings with famous Pentecostal pastors are promoted, you can find just as many advertisements where the names of imams and “ulama” (religious experts) who sponsor meetings and prayer sessions stand out aimed especially at the faithful. This assiduous advertising activity, initially adopted only by Pentecostal groups, is gradually absorbed by the Muslim community, also through social media, with the same flashy graphics and communication style.

If the success of many Pentecostal Churches, especially among young people, can also be attributed in part to the rhythms of the Gospel, which transform services into an interactive and engaging experience, even in “charismatic” mosques the element has begun to incorporate music.This practice unquestionably challenges any traditional dogmatism, according to which music and musical instruments are considered “haram” (forbidden) and consequently associated with evil activities. The choice of days dedicated to prayer also undergoes

a significant change.

The choice of days dedicated to prayer also undergoes a significant change. File swm

The adoption of the practice of carrying out Sunday prayers at the same times as Christian ones represents a clear adaptation to the needs of Nigerian society, where Sunday is a weekday and consequently more practical for the faithful than salat-al-jumu’a (Friday prayer) prescribed by Islamic rule. In addition to being justified as a way to avoid presenting oneself as less devout than Christians, “Islamic Sunday” poses a challenge to official institutions that still do not recognize Jumua

as a public holiday.

Furthermore, an extension of the duration of the “salat” (prayer) is observed. If in other traditional mosques, the prayer ends in no more than ten minutes, in the case of Nasfat it can last for hours, similar to long Pentecostal services. In addition, Christians are no longer the only ones who practice “Night Vigils”, or long sessions of nocturnal prayers. Today, in the streets of Lagos you can meet Muslims engaged in the same practice, as happens during “Laylat al-Qadr” (night of destiny) in the last days of Ramadan.

The reasons for change

From this picture, there emerges heartfelt anguish on the part of Muslim faithful at being marginalized and ostracized compared to their Christian compatriots in numerous aspects of public life in Nigeria. The incompatibility of some religious precepts with a society driven by a desire for progress and material realization means that these emerging Islamic groups transform, at least in part, the religious institution

into a business model.

Organizations such as Nasfat aim to train young Muslims who are educated and aware of their mission of spiritual awakening, but who are also active agents in the national public scene through “empowerment” activities aimed at strengthening their economic position.

“Islamic Sunday” poses a challenge to official institutions. File swm

Practical advice, loans and investments for small businesses offer concrete support to promote the economic development of the community, including through Tafsan (Nasfat in reverse), which is emerging as the fulcrum of the group’s financial activity. It is a multifunctional company that mainly deals with the organisation of pilgrimages and also with the production and sale of a malt-based non-alcoholic drink, Nasmalt, with more ambitious plans for the future, such as the establishment of a bank that operates in accordance with the principles of Islam.

Nasfat then organizes courses aimed at every segment of the population, including some dedicated to women’s activities. The latter begin to play important roles of power, comparable to those of the imams, arousing disapproval from the most fundamentalist faction of Islam but at the same time underlining an internal drive towards the reform and updating of the religion which therefore develops beyond simple competition with Pentecostal Christianity.

Lagos. It is one of the most complex realities in West Africa. File swm

In the charismatic reform of Islam promoted by Nasfat, a significant change is observed not only in religious practices but also in theological concepts. This transformation includes interpreting the Prophet Muhammad not only as a spiritual leader but also as an example of a successful businessman. Furthermore, similar to the conceptualization of spiritual warfare in Pentecostalism, charismatic Islam also recognizes the existence of a perpetual spiritual battle between beneficial and evil forces.The changes taking place within the Nigerian Muslim community, particularly in Lagos, are not unanimously shared by all the faithful. Clashes, theological discussions and disagreements on the part of followers and sometimes their leaders are frequent. Also, for this reason, the adoption of charismatic rhetoric and practices is not to be interpreted as a simple attempt to emulate the Pentecostals, but as an internal reform, promoted by agents who actively operate within the religious panorama of the country.

It is still an ambiguous process, which finds fertile ground for experimentation; a terrain that on a small scale reflects the entire context of Nigeria, where contradictory elements collide and different realities dialogue, continuously influencing each other.

Ahlam Taik