Ghana. Living Art in Tamale.

In recent years the inhabitants of this northern city have witnessed the birth of innovative cultural institutions that challenged conventions and brought contemporary arts closer to local communities.

Travelling from Accra to Tamale is like going to another country. The language, habits and geography itself are very different, similar to those of the Sahelian countries. Most southern Ghanaians have never set foot in Tamale, and don’t intend to. These premises are fundamental to understanding how revolutionary and exciting the recent developments that have occurred in the city are. Before diving into this scenario, it is useful to provide a little background.

Red Clay Studio in Tamale. Photo courtesy of Red Clay

At the turn of two millennia, the very essence of Ghanaian art began to be questioned with the accusation of being dated and neocolonial: in most cases, artistic production aimed mainly at creating goods to be sold to visitors and tourists.

Furthermore, the lack of economic support forced artists to rely on foreign patrons and platforms, often limiting the diffusion of what was considered art of a certain value. A collective of thinkers, artists and professors began to question the status quo. Coming from the art faculty of the Kwame Nkrumah School of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, they became known as blaxTARLINES Kumasi.

Renewal

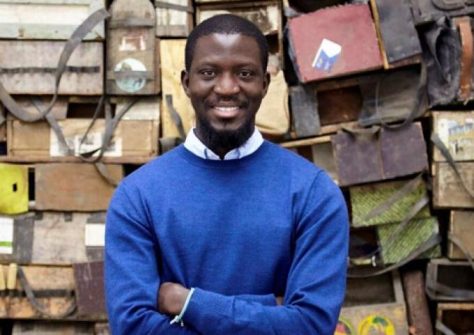

Led by teacher and artist Karî’kachä Seid’ou, the collective fought to redefine the narrative that surrounded and actually produced Ghanaian art. Specifically, their goal was to revolutionize the Ghanaian art space, empowering and challenging artists to explore new horizons. And the world took note: blaxTARLINES made Art Review’s annual Power100 list, a list of the industry’s 100 most influential figures globally. One particularly prolific student of blaxTARLINES Kumasi is Ibrahim Mahama: over the last decade, he has established himself as one of the most relevant contemporary artists in the world. His installations have been exhibited in the most important museums and institutions on the planet.

Ibrahim Mahama. Founder of the Savanna Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) and the Red Clay studio. CC BY 4.0/George Darrell.

Mahama, too, is originally from Tamale, and his work here is as grand as his enormous installations. In 2019, he founded the Savanna Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) and the Red Clay studio, soon followed by the purchase of an abandoned silo, now renamed Nkrumah Volini. Those who come to visit these places are struck first and foremost by the vastness of their dimensions. Large structures to display, discuss and create, spread across acres of land. These spaces are more than just artistic hubs: they are dynamic community centres that welcome local and international guests and connect them with the many students who come to visit them. Indeed, the endless flow of young people, whose minds seem enraptured by the experience, is as grand a sight as the spaces that host it. Mahama and his institutions place great importance on connecting with young people. One of the issues they have addressed with great commitment is that of transport. For primarily rural communities, getting to the centres can be a challenge. In this context, SCCA and the Red Clay studio are always ready to make shuttles available or provide funds for fuel: «In our vision, all this is done for the students, and transport cannot be an obstacle», explains Selom Kudje, director of SCCA.

Community Centres

Once logistical barriers have been overcome, Mahama says it is crucial to ensure that the community understands the value of the work done in the centres. Fishbone, the publisher of the popular blog Sanatu Zambang, dedicated to the arts and culture of northern Ghana, warns: «In the Tamale area, if a family has enough money to send their children to school, they do so in the hope that they will become teachers or nurses. Art is generally seen as a path of failure.” This is the reason why when Mahama gained notoriety, his art was seen as somehow foreign and aimed at foreigners.

Workshop with students at SCCA. Photo courtesy Scaa

Aware of these assumptions, Mahama has regularly organized conferences to bring the community together, to explain the vision and the art exhibited in its centres. The vision of photographer Nii Obodai, founder of Nuku Studio, is also on the same wavelength as Mahama, who also sees sustainability and connection with the community as priorities. His reality, housed inside an unused warehouse in Tamale, aims not only to provide a space that is available to photographers but also to foment the creation of an entire creative ecosystem, from publication to design to exhibition. Obodai also works to connect Tamale with other international showcases such as Addis Foto Fest, LagosPhoto and Johannesburg’s Market Photo. Nuku Studio collaborates with international institutions and develops locally sourced products to support its vision. At the heart is the connection between sustainability and community development, an approach that reflects Obodai’s commitment to making the creative industry an integral part of Tamale’s economy. All these collective efforts aim to create a space where art is not only a form of expression but also a catalyst for social change.

Routes of Rebellion. Vision Arts of Jesse Weaver Shipley. Photo courtesy Red Clay

The generosity, energy and desire to experiment and find a home in these places encourage young people to broaden their reach and redefine their function in society. The impact is profound, setting the foundation stones of Tamale’s cultural renaissance, which goes far beyond the confines of traditional art spaces. (Open Photo: Blindfolding The Sun and The Poetics Peace. A Retrospective of Agyeman Osei at the Savanna Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA). Photo: Elolo Bosoka/Courtesy SCCA.)

Benjamin Lebrave