Mauritania. Beyond the dunes.

The presidential elections, scheduled for June 22, constitute a test for the Mauritanian political system. The outgoing president,

Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, elected for the first time in 2019,

is widely expected to win.

The majority parties have designated him as their candidate ever since the announcement of the elections last December by the Independent National Electoral Commission (Ceni). The only opponent seems to be Biram Dah Abeid, the leader of the anti-slavery movement, already a candidate in 2014 and 2019 when he took second place behind Ghazouani. Ghazouani was the first president to be elected after a democratic transition in 2019, succeeding general Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, who had seized power with a coup d’état in 2008, was elected in 2009 and led the country for ten years. The conviction of Abdel Aziz for corruption and illicit enrichment las December made it possible to delve deeper into the nature of the Mauretanian political system.

Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, President of Mauritania. He is expected to win. CC BY-SA 4.0/European Union.

During the electoral campaign, the majority parties highlighted the government’s achievements on the social field in a country with strong disparities, improvement of infrastructure and services, steps taken to stem international terrorism, which has not hit the country for over a decade as well as the increase, in 2023, of the growth rate to 4.8% , after the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, the opposition forces accused the president and his ministers of not having broken with patronage practices, nepotism and corruption, of not having guaranteed fundamental freedoms and of not having improved conditions for the most fragile part of the population. They criticized the delays in the development of infrastructure, as evidenced by the disasters of recurring floods, the risk of drought and rising inflation.

Some parties have also contested the all-out Arabization, which has penalized black African populations who traditionally do not speak Arabic. A few weeks before the vote, the opposition, who appear divided, have expressed their concerns about the legitimacy of the elections given what has happened in the past.

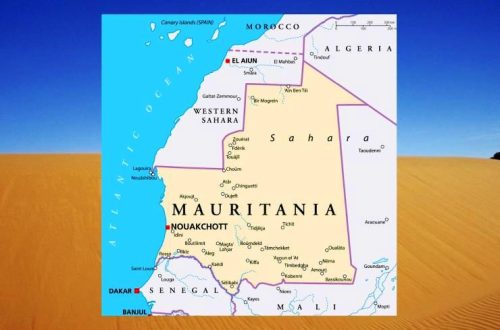

Mauritania Political Map with capital Nouakchott.123rf

In the meantime, there have been social tensions. At the beginning of February, a demonstration in Rkiz, in the south of the country, against the expropriation of former slaves’ lands by a tribal elite, provoked a very violent repression. “Land slavery”, as denounced by the militant anti-slavery deputy Biram Dah Abeid, is a recurring phenomenon. Racist clashes also extend to institutions.Recently the MP Mariem Cheikh Samba Dieng, an anti-slavery militant, was suspended from the National Assembly due to her accusations against the government, the words slavery and racism are taboo in the country. A demonstration in her favour in front of parliament was attacked by the police, resulting in injuries and arrests. Ahead of the elections, candidates are facing a climate of tension, socially and politically.

How society is made up

Two major cultural components make up the highly hierarchical Mauritanian society, an Arabic-speaking majority of Berber and Arabic origin, known as Maure, and a minority of Black-African origin, to which different ethnic groups and languages belong (Halpularen, Soninké and Wolof). The Maure are divided internally into the Beydan, the white elite, and the Haratin, the black-skinned slaves, now freed but who, despite the official abolition of slavery in 1981 and the introduction of the crime of slavery in 2007, continue to live in conditions of servitude

and discrimination.

Two major cultural components make up the Mauritanian society, an Arabic-speaking majority of Berber and Arabic origin, known as Maure. File swm

According to Walk Free’s Global Slavery Index, Mauritania ranks 3rd in the world, with 149,000 people out of almost 5 million inhabitants forced into slavery. The white elite implements strategies to occupy power in the state apparatus which, in a certain way, replace the ancient warrior and commercial vocation of these ethnic groups. Cronyism and corruption, as well as tribal membership, cement their relationship in society, useful for the consolidation of power and, in the event of any elections, consensus. Political parties become the institutional reference of the elite, but they are not the expression of a social base.There is substantial continuity between people and the interest groups that support them, despite the succession of roles or functions. First, the highest responsibilities in the administration – as in the economy – starting with the presidency, are the prerogative of the white Maura elite. This elite is itself criss-crossed by a certain antagonism, however never to the point of causing the system to implode. The strong man of the moment, whether by vote or coup, knows he must pay attention to the ethnic-tribal mix of positions of power, to establish alliances, through kinship, clientelism and the division of resources. The trial against Abdel Aziz partially exposed this system, which is significant, but it did not serve to undermine the mechanism on which power is based. According to the 2023 Corruption Perception Index, developed by Transparency International, Mauritania detains the 130th position out of 180 countries.

Flag of Mauritania on military uniform. 123rf

The role of the army.

A non-negligible fact, then, is the role of the armed forces which have always occupied positions of power whether through a coup or a vote. The current president Ghazouani is a former general and right-hand man of the former general-president Abdel Aziz. Military intervention in the Mauritanian situation seems to be driven by the need to act as an arbiter in the system when an equilibrium cannot be found within itself. The military is not interested in starting a new phase of “democracy” and “fight against corruption”, its interference simply guarantees that a balance is found and maintained so that the elite can continue to safeguard their own political and economic interests. (Photo: a touareg walking in the desert. 123rf)

Luciano Ardesi