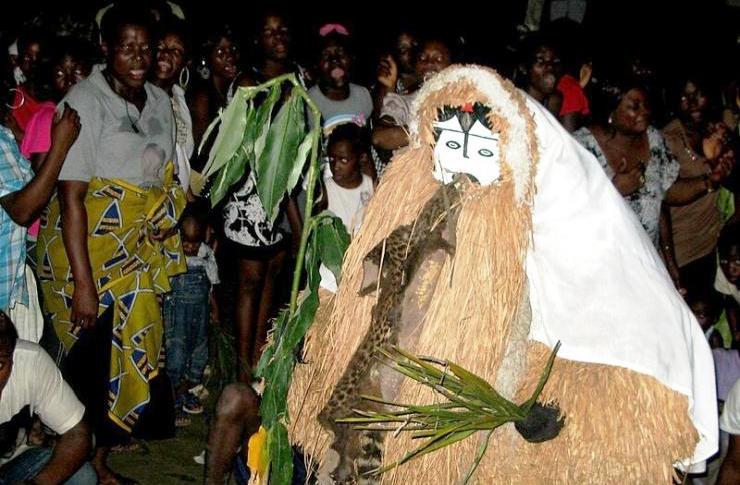

Equatorial Guinea – The Mekuyo clown.

The Ndowe people of Equatorial Guinea live along the banks of the Rio Muni. Of all their traditional feasts, the Mekuyo celebration stands out for its rich popular flavour. Any social event is a reason to celebrate.

The Mekuyo – the clown, as the Ndowe call him – is completely covered with small bamboo canes tied together; his hands and feet are covered by dark stockings. His face is a mask of bright colours: white, red, and black painted to make him look frightening.

Even though the celebration climaxes at dusk, the village awakens in the morning to the sound of typical songs: the Mekuyo and his assistants make the first round of the village to the beat of a drum.

The mid-morning is for the children. The Mekuyo walks through the village scaring and chasing boys and girls. They try to get away from him or to attract him by clapping their hands, shouting, and singing. Sometimes the Mekuyo runs towards the frightened children who scurry to take cover in a corner of the village; at other times, he makes signs to show he likes the children’s songs. While marching and singing they escort the important figure in fancy dress.

The Mekuyo walks through the village scaring and chasing boys and girls.CC BY-SA 3.0/ TheHungryCapitalist

If the Mekuyo falls or uncovers a hidden part of his body, everyone refrains from looking and commenting. Doing so would make them liable to punishment or to be cursed.

In the late afternoon, with the sun still high, the feast intensifies. First, the scene must be prepared. Any open space will do; the courtyard of the house where the feast is being celebrated is usually chosen.

There are many reasons for calling the Mekuyo: a wedding, a special social event, or a celebration of any kind. The family organising the feast provides the Mekuyo and his companions with plenty of drinks and liquor. They place a high seat or armchair in the centre of the courtyard as a throne for the Mekuyo. He sits there and, at the proper time, begins his frenzied moves and dances. In front of the throne, leaving plenty of space for people to dance, a hedge of vines or other plants is erected. The women gather near the fence, with a rhythmic dance they coax the Mekuyo to appear and entertain those present with his exciting movements. A bonfire is kept burning. It is an atypical bonfire in that the flames are hidden and only the smoke is seen. A large branch or small tree stands at the centre of the bonfire.

There are many reasons for calling the Mekuyo: a wedding, a special social event, or a celebration of any kind. CC BY-SA 3.0/ TheHungryCapitalist

The entire celebration takes place surrounded by the smoke of the bonfire, in the heat of the afternoon sun, and with the echoes of female singing.

The Mekuyo arrives at the courtyard with his entourage to the rhythm of the usual drum and goes towards the small house built for him. This hut must be very near where the feast takes place. It is concealed from prying eyes; only the Mekuyo’s comrades can enter. If a woman were to see what goes on in there, she would be severely punished. The same would happen if she should dare criticise the Mekuyo’s behaviour.

At the sound of the drum, the women begin their song waving one arm from above to below. The Mekuyo is about to come. He does not keep people waiting; he appears with his funny, exaggeratedly solemn gait and ridiculous gestures, with a green branch in either hand. He delights the spectators with some ridiculous moves and then takes his seat on the throne. The women intensify their song. Now the men, too, take part: with green branches in their hands, they approach the Mekuyo, inviting him with leaps and gestures to begin his dance.

A woman at the door of her house. Women shouldn’t enter the dance – it is only for adult males. 123rf

At first, the Mekuyo pretends to take no notice. He soon begins to grow restless, and finally launches into a spasmodic dance, shaking frenetically like an electric puppet.

The people are now enthusiastic with this success but suddenly the Mekuyo makes an abrupt gesture and stops. The whole process must begin all over again: the women’s songs, the men’s gestures and, finally, the Mekuyo’s dance. During the afternoon, several different Mekuyos appear, up to four or five. One after the other, they repeat the same scene; at times they may act all together. The feast goes on for three or four hours without a break. It climaxes as night falls. Instead of branches the Mekuyo gather glowing firebrands. The leaps and dances become increasingly impressive – drinks inevitably play their part. Then, slowly, with no further ado, the feast dies away and ends with darkness.

Women shouldn’t enter the dance enclosure – it is only for adult males. Women enliven the feast with songs and dances.

All the same, women enter for the briefest of moments; they dance differently to the men and, before going back to their places, offer a small gift to soothe the men’s indignation, usually a coin. Also, boys cannot approach the Mekuyo. Their role is to flee, pretending to be frightened. When they approach adolescence their fathers or some male family member introduces them to the secret of the Mekuyo. From then on, they can take part in the dances with the other men. No one, not even the women, can ask them to reveal the secret. If they are questioned, they will not answer but will express great anger and, perhaps, if the question comes from someone younger, will slap them.

The Mekuyo originated outside the ethnic groups that now practice it. CC BY-SA 3.0/ TheHungryCapitalist

Where does the Mekuyo originate? What do the theatrics mean? What does it mean to the Ndowe today? Without doubt, it is ritual and symbolic. The Ndowe say very little about the Mekuyo. They only say it describes the participants’ roles. The rest is secret.

The Mekuyo originated outside the ethnic groups that now practise it. It began along the coast of Gabon, expanding towards the north. In the middle of the XIX century, it reached Kogo and Corisco and, in the XX century the Ndowe of Bata and its surroundings. Compared with other Ndowe traditions of the area bordering on Cameroon (Bevala, Mokuku), it is different: celebrated by day and often with the whole village participating. It lasts for just one day and the magical element is minimal. It is not associated with other curative or religious rites. At first sight, it could be related to events highlighting male courage. For this, women and children are excluded.

Some legends speak of a forest animal that accidentally came across a woman and asked her to take it to the village. She was frightened and did not dare to; instead, she ran to the village to tell what had happened. The men coaxed the animal into the village and played with it. Others speak of a bear that terrorised a village until the courageous men captured it, making it fall into a trap. They carried it to the village and showed off their courage while teasing the animal.

(Open Photo: The Mekuyo. CC BY-SA 3.0/ TheHungryCapitalist)

Felipe R. Aron