Electronic Africa Continues to Evolve.

The way electronic music entered the African scene in the 1990s, how it was developed, and how it is becoming increasingly relevant. From kuduro in Angola to gqom in South Africa.

Two factors occurred in the 1990s that created the space for the entry of electronic sounds into the African musical panorama. Since the 1980s, analogue recording studios began to close due to the collapse in vinyl sales with the boom in pirated cassettes. At the same time, digital studios and their distribution formats have not yet taken hold, and therefore in many African countries, there is a sharp decline in the production of recorded music.

In the same years, radio frequencies were liberalized in various states, and many new stations were created in many of the large capitals, heralding a new phase in which the demand for music skyrocketed, satisfied mostly by foreign music, often Western, precisely in the years where house, techno and dance genres start to go crazy. This is the context in which in 1994 the hit I Like to Move It by Reel II Real reached the airwaves of Angola, where it led to the birth of what later became the symbolic genre in the country, kuduro.

Kuduro has become the distinctive sound of Angolan youth. File swm

Young Angolans imitate the sound of the hit, which in turn recalls their local rhythms, using simple tools such as a cell phone with personalized ringtones. In the following years, small digital studios popped up all over Luanda and kuduro, with its hard and essential electronic beat, became the distinctive sound of Angolan youth.

Even in Ghana the wave of house and dance music, called asokpor, gradually absorbs local rhythms, taken mainly from the jama and kpanlogo dances and rhythms of the Ga people. In South Africa, house in its original form is a long-lived and dominant genre; still in vogue since the 1990s, it contributed to the breaking down of the barriers imposed by apartheid and gave rise to kwaito.

This slowed-down, socially conscious, take on house incorporates South African elements, particularly Zulu rhythms and hip-hop vocal styles.

An alternative sound

In the 2000s, a new, deeper form of Afrohouse emerged, with softer, more expressive singing and more delicate beats. The standard-bearer of this new trend is Black Coffee, probably the most popular African DJ in the world; he and other DJs have achieved superstar status in South Africa. However, as commercial success increases, the sound becomes economically inaccessible for new producers.

At the beginning of the 2010s, the need for alternative sounds emerged. Instead of polite rhythms and sophisticated – and expensive – vocals taken from established artists, local producers created the onomatopoeic gqom style, marked by essential, minimal, and repetitive arrangements reminiscent of Detroit techno and industrial music.

Black Coffee (left) performing with DJ Shimza. CC BY-SA 4.0/Andy Vuyo

Gqom started in South Africa, expanding across the continent and beyond, with gqom parties in many European cities. People had hardly become used to it, however, when a substitute took hold in the motherland, this time the more durable amapiano, literally ‘very piano’ in the Zulu language, which emerged in the mid-2010s. The tempo is slower than gqom or house music, the beats are softer, and the instruments have a more organic sound. Having gone further than any of its predecessors, the amapiano livens up parties in Lagos and Nairobi but also in London and Milan, and endless dance videos with amapiano music appear on TikTok, spreading its sound and culture.The sound spread to other African countries. Nigeria, musically the undisputed heavyweight champion, adopted its Afrobeat to create Afropiano.

Lubumbashi, in the DR Congo, is home to a vibrant Afrohouse and also an Amapiano scene, which began a decade ago with DJ Spilulu, and in more recent times led by DJ P2N and DJ Renaldo.

Angola remains permeable to South African house influences, with producers like Djeff touring the world.

“The growing influence of music created in Africa is a reminder of the cultural strength of a continent”123rf

In Ghana, there is no autonomous house scene, but some visionary producers work in Accra, such as Nshona Muzick, the main creator of the vogue for dance and azonto music that in 2012 spread across the country and among the diasporas.

The same economic obstacles that contributed to the birth of gqom in South Africa recently led to the birth of a new electronic genre in Nigeria: cruise, from the slang phrase catching cruise, literally ‘having a laugh’. Here too, producers replace expensive vocals with snippets of audio taken from online videos. Everyone from politicians to street vendors ends up listening to fast, stripped-down beats.

The countries mentioned all have a long tradition of adapting their musical environment to new instruments, trends, and aesthetic tastes. In other areas of the continent, electronic contaminations remain more experimental, more underground, but the musical scenes in which they develop are no less rich for that.

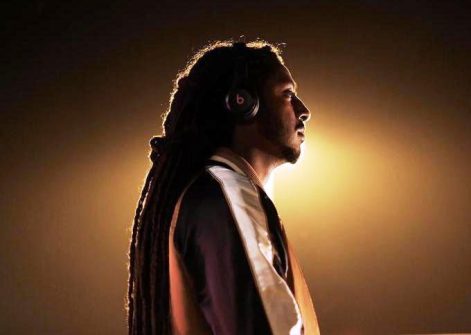

Rophnan Nuri Muzeyin known as Rophnan is an Ethiopian musician, singer, songwriter, DJ, and audio engineer. CC BY-SA 4.0/Cymande25th

Uganda is emblematic: in the capital Kampala, the Nyege Nyege festival and label drives electronic experimentation and creates connections between local artists and international situations. The Electrafrique nights, on the other hand, born in Nairobi and now at home in Dakar, are a lively hub for Afrohouse and other electronic styles. The Afro-futurist artist and producer Ibaaku works in Senegal; Chad is the home of Afrotronix, while in Ethiopia, Rophnan has become a star for having projected his traditional training into new and daring electronic productions. There are many more artists, and the creativity and opportunities that characterize the scene show no sign of decreasing. In an age where migrants are in the headlines and visas are denied, the growing influence of music created in Africa is a reminder of the cultural strength of a continent we too often overlook. (Open Photo: 123rf)

Benjamin Lebrave