Mauritania. Caught in the Nets of the Fishing Mafia.

The fishing tradition goes back a long way in Mauritania. But as more and more Chinese fishmeal factories have set up in the country, local fishermen are often left empty-handed. This unscrupulous business threatens the basic supply of the Mauritanian population.

At first glance, the Mauritanian fishing village of Nouamghar, about 150 kilometres northeast of the capital Nouakchott, appears deserted. A few dozen simple houses are scattered along the beach. The waves of the Atlantic hammer their facades, and the plaster is peeling off everywhere. Some families prefer to live in traditional tents, surrounded by fences made of fishing nets to protect their privacy.It is early in the morning and silence reigns in the house of 69-year-old Sheikh Muhammed Salim Biram. The white-bearded man, a former fisherman, is sitting on the floor outside the living room, tying a new net.

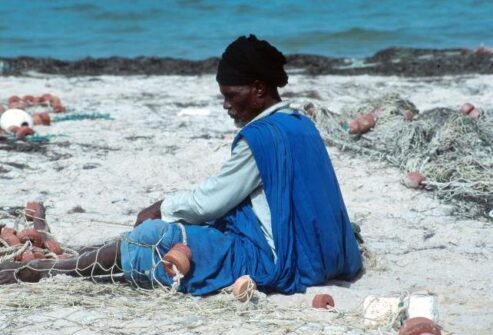

In Nouamghar, people have made their living from fishing for generations. Photo: Swm

In Nouamghar, people have made their living from fishing for generations. “In the past, the fishes used to come very close to the beach” says the sheikh. Today the fishermen go far out on the sea and often come back empty handed”. His two sons listen to their father’s words, without daring to interrupt him.

The old man continues: “My neighbours come to me and complain because they haven’t caught anything. But what can I do against the government?”. The sheikh believes the blame for the disappearance of the fish lies with the politicians. “They brought the Chinese into the country – he grumbles -. They steal our fish and make meals for their pigs while our people don’t have enough to eat”.

Coveted fishing grounds

The abundance of Mauritanian fish has sparked a craving for fishing over the last century. At first, Europeans fished off the almost 600 km-long Atlantic coast. For some years now, trawlers from all over the world have been fishing in the waters off West Africa. Most of them fly the Chinese flag. But the most lucrative business takes place on land, in factories hidden behind high walls and protected by armed guards.

In Nouadhibou which is Mauritania’s second largest city and serves as an important trading centre, some 550,000 tonnes of fish are processed into fishmeal and fish oil each year, and 130,000 tonnes of fishmeal are exported. Fishmeal is rich in protein, mainly used in fish farming, but also in animal fattening. Almost a quarter of the world’s wild fish is processed into fishmeal.

Almost a quarter of the world’s wild fish is processed into fishmeal. Photo: Swm

“There are 30 fishmeal factories in the city and another ten in southern Mauritania. It is evident that there are too many; our neighbour Morocco, which has a coastline twice as long as ours, only has ten,” says Aziz Boughourbal, managing director of Mauritanian Holding Pelagic. He goes on to say: “Although every fishmeal producer must also produce fish for consumption, most of the big fishmeal producers do not”. Boughourbal’s company has its own fishing boats but also buys from traditional dugout boats that moor in an anchorage about 80 meters from the shore. There, the fish are sucked up and pumped through a pipeline to the factory. A conveyor belt then transports the fish into cylinders where they are steamed at 95 degrees. When the sardine shoals are ready, the Boughourbal factory can ramp up production to 400 tons of sardines per day. The product is packed in phylogram bags and shipped to Japan, Russia, and the EU.

The sea smells

Most of the factories are located on a promontory behind the local fishing port. A paved road, “Fishmeal Avenue”, is lined with trucks that bring fish from the port. Eight factories are located right next to the port, where fishing boats are also repaired. “Foreigners are not welcome here. They have brought us nothing but trouble”, says boat builder Muhammed Fal. “First of all, the Chinese, who pollute the sea here with impunity”. He points to the warehouses of the Chinese SFHP fishmeal factory, hidden behind a yellow wall. From a hose coming out of the factory, the reddish and smelly water pours into the sea.

“They pour all the dirt into the bay”, Muktar Nguye tells us. The 26-year-old has just returned from fishing with his pirogue, with about two tons of mullet on board. “In the past, we rarely went home with less than six tons”, the young man says.

Chinese fishing vessels outnumber the small fishing vessels. Photo: Swm

He could get 25,000 Ouguiyas, about 600 Euros, for the catch. “I have to use it to pay for fuel and six crew”. Nguye used to fish mainly for sardines but there aren’t enough anymore, he says. Chinese fishing vessels outnumber the small fishing vessels. It’s not the competition in fishing that annoys Nguye, but the lack of respect for people and the environment: “They dump used oil, diesel and plastic residue into the water” says Nguye. “The sea stinks and the smell scares the fish away”.

He steers his dugout close to shore, where his men wait in waist-deep water with empty plastic crates on their heads. They fill them with fish and walk ashore to unload the fish onto the flatbed of an antique Peugeot 404. An hour later, Nguye’s boat is empty. He collects his money and goes home.

He lives with two older brothers, their wives, and children on the outskirts of town; the house is only half finished. Space is scarce, and each family occupies a room. “We want to add a floor – says the fisherman – but lately the fishing has been poor and we don’t have the money”.Nguye is a member of the National Fishermen’s Association (FNP), where he advocates for fishermen’s interests. Here their concerns are taken seriously. “There is a war going on out there” says FNP chairman Sid’ahmed Abeid. “We are still enduring everything, but sooner or later, the fishermen will rebel”.

Eventually, the government must intervene, he says, because the Chinese do not respect the closure periods or protected zones. “And when they are stopped, they invoke the treaties and threaten the intervention of the embassy or of their government”, he points out.

The government avoids conflict with China because the country depends on finance flowing from Beijing. Already in 2006, China and Mauritania concluded a cooperation agreement. As a result, the Chinese have financed about 40 projects across the country, including the international airport and the new foreign ministry.

A Chinese world of its own

In Nouadhibou, the Chinese have been living in a parallel universe for years. Except in their factories, they have almost no contact with the locals. On the main road, there are numerous shops selling items imported from China.

There are a dozen Chinese restaurants in the city that also serve beer, vodka and the Chinese liquor called baijiu, despite Sharia laws.

Most Chinese travel to Mauritania to make money. After a few years, they return to China or move on to another African country.

Many locals are unhappy with the privileges the central government has granted to China. Photo: Swm

Many locals are unhappy with the privileges the central government has granted to China’s Poly Hong Dong fishmeal factory, for example, which has close ties to the Chinese People’s Army. It obtained the license to produce fishmeal under undisclosed conditions. It was allowed to build its own fish farm directly across from the factory. The Chinese company owes this permission to its local partner who does business with the presidential family. In Mauritania, foreign factories must have a local partner because foreigners are not allowed to buy or lease land. Local companies lease the land and take part of the profits – a business that could hardly be more lucrative.

Lawless spaces

“The factories have powerful local backers,” says Malum Obet. A high school teacher who is part of a popular group that reports violations by fishmeal factories. The group conducted an investigation and found that only three Nouadhibou producers are complying with the law. No Chinese factories were among them. Obet says, “The Chinese are poisoning the population and treating their workers like slaves. Although the law requires it, many workers do not have a contract. As day laborers, they sometimes work 16-hour days, with no additional pay. Nevertheless, many people queue up for work because there are no other jobs in the area”.

An industrial zone is planned to be built 60 kilometres north of the capital where new Chinese fishmeal factories are to be built. Photo: Swm

The government of President Mohamed Ould Ghazouanie, by and large, keeps out of the conflict. Mohamed Salem Louly, the adviser to the fisheries minister, says they are aware of the danger of overfishing.

For this reason, the ministry, together with the Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries Research, has determined the catch levels at which stocks can grow sustainably. On this basis, quotas were set well below the critical limits.The reality is different because the Coast Guard lacks the money for patrolling. And the situation could get worse. An industrial zone is planned to be built 60 kilometres north of the capital where new Chinese fishmeal factories are to be built.

In Nouamghar, people can feel the effects of the crisis. “Young people are leaving the village because there is not enough work”, said Sheikh Muhammed Biram. “Some are trying to emigrate to Europe”. His children are also waiting for an opportunity to leave. Some friends have tried to reach the Canary Islands in a wooden boat, crossing the Atlantic for 1,000 kilometres. But not all of them arrived safely.

Andrzej Rybak/Kontinente