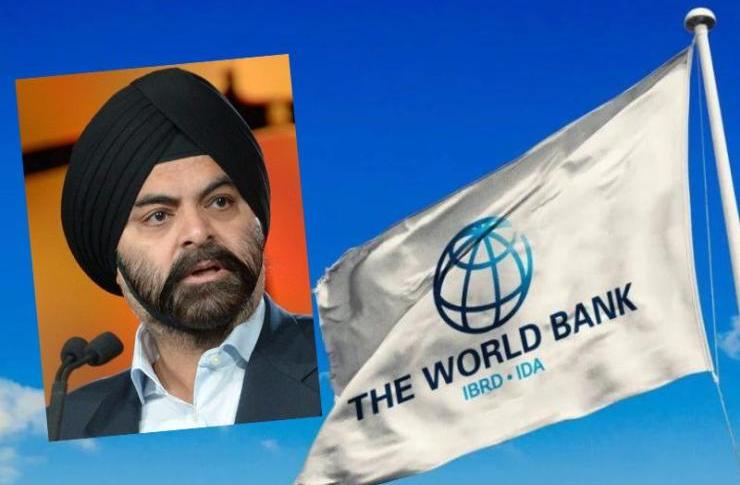

World Bank. New President, Old Doubts.

Marrakech will host the annual assemblies of the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from 9 to 15 October. The event, which marks a return to Africa comes 50 years after the assembly in Kenya. This time the World Bank will be led by a new president. Ajay Banga’s new course faces three challenges: competition with the banks of China and BRICS, involving

private finance, combining efforts against climate change

and the fight against poverty.

The World Bank (WB) – strongly controlled by the USA with a majority share of over 17% – and its president, always nominated by the American administration, cannot fail to take into account the directives coming from Washington. This will also be the case for the new president, who will naturally want to make his personal contribution and at the same time take into consideration, at least in part, the proposals and policies of the other member countries.

The brief declarations of appreciation for the appointment of Ajay Banga – elected on May 3 – by President Joe Biden and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, help to understand the new mission. Biden highlighted that Banga “Is uniquely equipped to lead the World Bank at this critical moment in history. He has spent more than three decades building and running successful global companies, creating jobs, and driving investment in developing economies, and guiding organizations through periods of fundamental change. He has a proven track record of managing people and systems and working with global leaders around the world to deliver results”.

President Joe Biden and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. Photo. Usa Gov.

Biden will support his efforts to transform the World Bank, which “Remains one of humanity’s most important institutions for reducing poverty and expanding prosperity around the world”. For her part, Yellen noted the ability of the new president to mobilize resources and public and private partnerships to face the most urgent issues of our time, including global warming.

As chairman of the World Bank Group, Banga also becomes chairman of the Board of Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).

In competition with two banks

His first task will be geopolitical since it is the ongoing economic, political, and military conflicts that determine the redefinition of global power. The WB will be strengthened to benchmark and blunt the international operations of two other emerging banks, China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), with India as its second-largest shareholder, and the New Development Bank (NDB), created by the group of BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa).

The headquarters of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in Beijing,. CC BY-SA 4.0/ N509FZ

The AIIB is also the banking and financial instrument of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the so-called New Silk Road, which finances development and infrastructure projects, especially in much of Asia. It undoubtedly reflects Chinese economic and geopolitical interests, but at the same time, it is already able to respond, in part, to the many requests for development from poor countries, especially in Africa.

During the 2019-20 fiscal year, the World Bank disbursed $14.5 billion to Africa, but only a small fraction of that went towards building new infrastructure.By comparison, the African Development Bank (AfDB) disbursed $5.1 billion, most of which went to infrastructure.

In the same year, the AIIB paid $6.23 billion to its Asian members for green infrastructure projects in the fields of energy, water,

and urban development.

The logo of the NDB in the bank’s HQ in Shanghai. CC BY-SA 4.0/ Bb3015

The NDB promotes agro-industrial and infrastructural projects and trade exchanges between the BRICS countries and places the support and involvement of poor and emerging countries among its priorities. In fact, the two banks cover the shortcomings of the WB and in many cases replace it. Furthermore, in their trade and investments they favour the use of local currencies, bypassing the dollar.

They do so not out of a mere anti-American spirit, but because after the Great Crisis of 2008, they know that the entire international financial and monetary system, born in Bretton Woods, is in free fall, and they do not want to be crushed by it.

Challenges and false steps

In the geopolitical operation, Banga will focus on Africa, which will increasingly be the continent where the forces fighting for global hegemony will collide. His international profile is perfect, he knows and frequents world leaders, in recent years he has worked a lot with several African countries and, if necessary, can play the card of his Indian origins, the largest developing country. It is no coincidence that he made a long journey of contacts in many states, especially those of Africa such as Kenya, Ghana and the Ivory Coast, to promote his candidacy.

The second task of the new president is to involve the private financial sector in the activities of the World Bank. “There’s not enough money without the private sector,” he told reporters last March. No one could be against private aid and investment. The real question is one of money for whom and for what really controls and drives operations.

Kenya. Nairobi. In recent years Ajay Banga has worked a lot with several African countries. Photo Swm.

Undoubtedly Banga has vast experience in the field of finance, in particular, however, in the speculative sort, the type that is greedy and insensitive to the needs of the poor and of those who have to fight to improve their basic living conditions. His entourage lets it be known that it is intended to distinguish poor countries from those with acceptable development. The former would depend only on the subsidised credits of the IDA, while the latter, which sometimes already venture into international markets to sell their bonds, could be involved in some form of ‘creative finance’. It is feared that IDA funds will become increasingly scarce in the future.

His previous experience as a MasterCard executive in South Africa can be enlightening. In 2016, he made an agreement with the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) and with Net1, a financial services company owned by BM, and with its subsidiary Cash Paymaster Service (CPS) to use MasterCard debit cards for the distribution of pensions and other state benefits.

It was supposed to be an initiative of greater administrative efficiency in support of destitute citizens who in this way could avoid endless queues at the counters, possible muggings, and other problems. It was greeted positively by all as an example of inclusion.

South Africa. Shopping Centre in Johannesburg. When Ajay Banga was a MasterCard executive in South Africa, he made an agreement with the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) and with Net1, to use MasterCard debit cards for the distribution of pensions and other state benefits. Photo.Swm

It was an experiment for a potential pool of 500 million people worldwide. It should be borne in mind that, until the end of the last century, the World Bank was openly opposed to electronic money transfers as it feared that they would negatively alter the consumption patterns of the poorest people. The second step, however, was to collect the personal data of at least 18 million citizens. On the basis of this vast source, a series of offers of contracts of various types, small insurances, such as those for funerals, telephone subscriptions, etc. was instigated.

Monthly payments for these services were automatically deducted from debit cards. However, many citizens soon found themselves in great difficulty when they realized that there was very little left for day-to-day living. The most dangerous element was the entry of financial engineering. Given that the flow of money was guaranteed by the state, those who issued the debit cards, the insurance companies and the other financial services involved behaved, in fact, like uncontrolled banks, the so-called shadow banking, and started with securitization, i.e., the issuance of securities based on the value of the contracts in their possession. This is exactly what happened in the 2008 crisis with subprime mortgages and the creation of the gigantic bubble of financial derivatives issued on real estate mortgages. In 2020, the CPS

filed for bankruptcy.

Climate change and poverty

The third task concerns the role of the World Bank in the face of climate change. Banga has said that “poverty reduction and shared prosperity cannot be separated from the challenges of managing nature”. A sacrosanct principle on paper. We need to see how it is handled in reality because not all parts of the world are the same. The Bank’s roughly $100 billion a year to help developing countries cope with climate change is well short of the trillion needed. Many developing nations fear that the focus on climate change will divert attention from the fight against poverty. These countries have been hit hard by the pandemic, rising food and energy prices, and unsustainable debt levels.

It must be noted that on the African continent, a large part of budget expenditure is covered by revenues from energy sources, such as oil, gas and coal, or other raw materials.

Many developing nations fear that the focus on climate change will divert attention from the fight against poverty. 123rf.com

This aspect must be duly taken into account in the so-called green transition. In this regard, we must remember that the centre of global pollution is elsewhere. According to estimates by the International Energy Agency (IEA), in 2050 the United States, China and India together will generate CO2 emissions equal to 42% of the total, more than Africa, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East, combined. It would be unacceptable if under the presidency of Banga – a former advisor of BeyondNetZero, the climate change fund of General Atlantic, of which he was vice president – the WB used the ‘ecological yardstick’ to condition its interventions and its investments in the poor countries of Africa. We must bear in mind that its current mission is to end extreme poverty and improve the living conditions of 40% of the citizens of each country who live at the lowest end of income distribution. (Open Photo: Ajay Banga, 14th President of the World Bank Group. WB)

Paolo Raimondi