DR Congo. Lake Kivu. The Explosive Secret.

It is one of the most dangerous basins in the world for the gases contained in its seabed and for the possibility, not only theoretical, of explosions. For once, the extraction of gas would be considered a beneficial action. The first concessions have already been awarded. A danger could come from a possible conflict between Rwanda

and the DR Congo.

“At the bottom of the lake, where it is impossible to see, there are dark waters. According to legends, the darkness extends endlessly; there is no bottom, and that’s where Mami Wata can drag you down”. In a village south of Gisenyi, on the Rwandan shores of Lake Kivu, the old fisherman Maurice Gahanage is arranging his nets after a morning of hard work while evoking in Kinyarwanda the legends associated with this body of water, one of the largest in Africa, located on the border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Maurice says he knows all the secrets of the lake. He grew up on pirogues which have kept the same shape for hundreds of years, characterized by long wooden arms on the sides which extend into the water to lower the nets and on which oil lanterns are hung to attract the isambaza at night (fish measuring a maximum of 5 cm, which the inhabitants of the lake area are fond of).

“When someone disappears while swimming, we know what has happened”, says the fisherman. “You may get cramps or feel like you are suffocating from strange exhalations that suck you down. It is the guardian deity of Kivu who takes you with her”.

Fishermen in Lake Kivu. CC BY-SA 4.0/Isma250

A few kilometres away, in Nyamyumba, young Samuel Manizabayo – who ferries goods, people and tourists across the lake – also states that it is not uncommon to smell a strange toxic smell coming out of these waters, especially when passing near the ‘Akarwa ka bakobwa’ rocks about 500 meters farther out.

“According to the stories that our grandparents have handed down to us, those who committed serious acts, such as adultery or murder, were once abandoned on those rocks. Legend says that the lake would take them away to punish them”. Along the coast, tourist resorts for the rich and wealthy alternate with modest fishing/farmer villages perched on the hills, covered with terraces, and where bananas, maize, beans, coffee, and tea are grown.

The lake has always been an indispensable source of livelihood for the provinces of Rubavu and Rutsiro and part of the cultural roots of the population, so an aura of mystery has been created about it.

A dangerous lake

Apart from the legends, Lake Kivu really does hide a very ominous secret and is one of the potentially most dangerous lakes in the world. A geological anomaly caused by its depth and the intense volcanic activity surrounding it, this body of water of more than 2,700 km² contains in its depths 300 km³ of dissolved carbon dioxide and 60 km³ of methane, mixed with toxic hydrogen sulphide.

It is a lake in which a rare phenomenon that geologists call a limnic eruption could potentially take place, i.e., the explosive and sudden release of these gases into the atmosphere. According to scholars’ estimates, the lake contains the equivalent of 2.6 gigatonnes of CO2, equal to about 5% of global annual greenhouse gas emissions. In this event, a cloud of toxic gas would spread over the surrounding territories killing millions of people in minutes, as the region is densely populated.

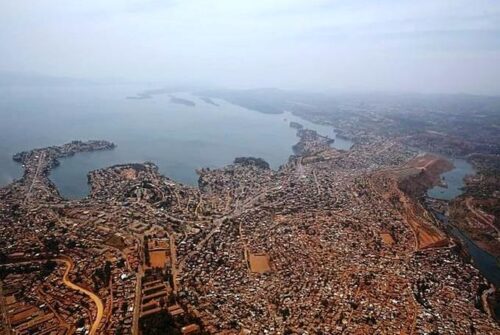

The city of Bukavu & Lake Kivu – South Kivu. CC BY-SA 40/Abel Kavanagh

The city of Gisenyi is located exactly on the border with the DR Congo and if it weren’t for the border, it would be one with Goma, the capital of the Congolese province of North Kivu, with over 2 million inhabitants. These two inhabited centres are at the foot of one of the most active volcanoes in the world, Nyiragongo. On 22 May 2021, the lava lake present in the volcano (which has been erupting since 2002) came out with lava flows that headed for Goma, destroying several villages causing 32 victims and 450,000 displaced people. On that occasion, many experts had feared the worst, but fortunately nothing serious happened.

People have always wondered about the probability of the lake ‘exploding’ and scientists are divided on its stability. Although the lakes in the world thought to be capable of limnic eruptions are quite rare, everyone remembers what happened in 1986 in Cameroon, when Lake Nyos exploded releasing over 100,000 tons of CO2 in the Subum and Fang valleys, killing 1,746 people and thousands of animals.

Environmental physicist Augusta Umutoni, former program manager of the Lake Kivu Monitoring Program (LKMP) and now a consultant, explains that the gases are held back by the pressure of the water at a depth of over 300 metres and that “the risks of eruption are real but reduced, estimated at around 55%, which corresponds to the saturation level of dissolved gases in the lake at present”.

Lake Kivu, boats. CC BY-SA 4.0/Steve Evans

According to a study published in 2015, the last limnic eruption of Kivu occurred between 750 and 1,000 years ago and most scientists believe that a major earthquake, landslide, or volcanic eruption of Nyiragongo could trigger a gas release, upsetting the structure of gradients in the depths or increasing the saturation of the lake. “These should be events of enormous proportions because the lake is among the deepest in the world and its conformation is different from that of Nyos which was then saturated”, underlines the sceptical Dario Tedesco, a volcanologist at the University of Naples (Italy). For the researcher “it is more probable that a volcanic eruption on the bottom of the Kivu could cause a limnic explosion given that it is located on a branch of the Rift Valley (African Rift Valley, ed) or, and there is really something to fear about this, that ‘human activity’ may disturb the equilibrium of the lake”.

De-saturate the water

The Italian researcher refers to the possible solution proposed by many to prevent a catastrophe, which consists of extracting part of the gas to de-saturate the water. Among other things, methane is a fossil fuel that would produce the electricity that the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda needs. Indeed, the stakes are high: researchers have estimated that methane in Lake Kivu could yield up to $42 billion over 50 years. In a world where the aim is to reduce the use of fossil resources and where people criticise African countries that would like to use them for their development, this could perhaps be the only case in which extraction would even be considered beneficial.

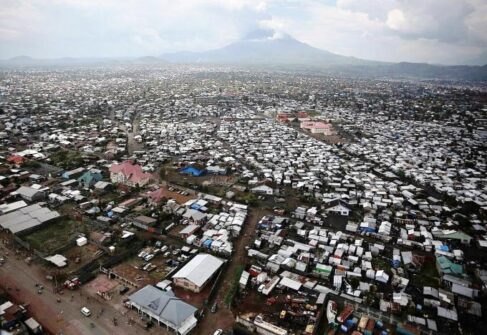

The city Goma and volcano Nyiragongo in background, North Kivu. Photo: CC BY-SA 2.0/Abel Kavanagh

Currently, in Rwanda there is a functioning 26 MW plant operating since 2016 with the KivuWatt project of the Americans of ConturGlobal. This plant extracts the gaseous waters from over 260 meters deep, separates them from the gases and pours the degassed waters down into the various density layers of the lake. The retained methane is then piped to a coastal power plant.

The race for gas and questions arising

After the 2021 eruptions, the Kivu gas rush got a boost. This can be seen as you drive south from Gisenyi along the coast road, along which cranes and barges lay huge steel pipes. These are the construction sites of the new projects of the Rwandan Shema Power and of the Kivu 56 plant which will soon come onstream. Even in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, things are moving, and extraction will soon begin thanks to the concessions granted to three North American companies. There are, however, some question marks.

CC BY-SA 2.0/ Martijn.Munneke

First, not all scientists agree on which gas extraction technique is the best to avoid disturbing the balance of the lake. Secondly, “these operations should be monitored continuously, with data exchanges between companies and between the two countries which, however, are at loggerheads”, says Professor Tedesco.

Umutoni also echoes him: “The competition for the exploitation of the resource combined with the growing tension in the area could interrupt bilateral cooperation on the harmonization of methods and regulations. That’s what we fear the most”.

Lake Kivu is indeed located in an unstable region, battered by decades of conflict and turbulent history due to its immense natural resources. In recent months, clashes between the Congolese army and the M23 rebel group have exploded in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These actions have caused hundreds of victims and thousands of displaced people. Kinshasa has long accused Rwanda of backing the M23 group, but Kigali has always denied it.

Sunset Lake Kivu. CC BY-SA 4.0/ Bintu utuje

“If this outbreak were to escalate into a direct conflict between Kinshasa and Kigali, there would be serious repercussions for the safety of the lake during the mining operations for which a competitive race has begun”, says Onesphore Sematumba, an analyst at the International Crisis Group. Meanwhile at anchor in a small gulf in Kigufi, the fisherman Maurice and his crewmates prepare for a customary night of fishing. He too observes Goma in the distance and the barges of the gas extraction yards. “We were told that gas extraction should keep us safer and bring down electricity costs. But what if nature rebels one day? What if Mami Wata does something? You can’t fight fate”. (Open Photo:123rf)

Marco Simoncelli